Where do good ideas come from? Is there a science to innovation? How important is intuition and imagination?

I talked to Josh Lee, who is Vice President of Product Management at Fashionphile, an ultra-luxury designer handbag exchange. Josh and I worked together when he was our client at Nordstrom. Josh is an expert in creativity; an innovator and inventor. And lucky for you, I talked to him about the science of good ideas.

Josh, where do ideas come from?

During a Q&A part of a lecture, I once asked Professor Fred Collopy (renowned in Design Thinking, Cognitive Science, and Information Systems) a common question that was being debated amongst students – “Where does design start – at inception (sparked by a catalyst/problem) or with instinct (natural, like a bird building a nest)?” His answer was, “What’s measurable?” I said, “I guess only inception.” He then said, “If you can’t measure it, then who cares?” The point is to be able to definitively say that something is either working, or more interestingly, what’s NOT working.

Innovation, as we know it, comes from a catalyst – something we have experienced or someone else who has experienced and shares their story. Designers, engineers, or inventors will often speak of empathy being a pillar of their practice, in order to understand these problems, and when it’s found, regard the problem as the focal point of their innovation.

How do you spot a good idea?

The best ideas, or high impact ideas, address impossible problems that profoundly affect peoples’ everyday life. We find traces to these problems in experiences – and as researchers, we create feelers for these experiences through studies. (See Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning, Rittel & Webber)

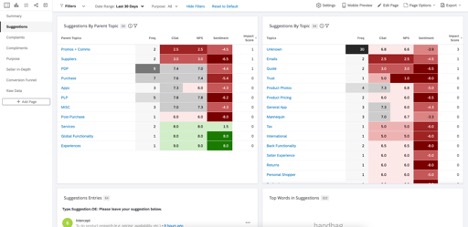

In retail, we have several means of soliciting these traces in the shopping experience. At Nordstrom & Fashionphile, we have set up “constant telemetry” around all the main parts of the experience which we call “lanes,” such as search & discovery lane, checkout lane, post-purchase lane, and the account management lane. The scoring of NPS (Net Promoter Score) and CSat (Customer Satisfaction) create a standardized numeric system to weight the topics. We consume and filter the topics through NLP (Natural Language Processing), which takes complex open-ended text into classifiable topics in the system. This operation is a constant stream, which allows us to know- through time- what the biggest issues are at the moment – and these topics often start as a start to where to begin digging.

Josh shared an example that operationalizes Csat, NPS, Brand Sentiment into a dashboard based on customer feedback topics.

What about bad ideas?

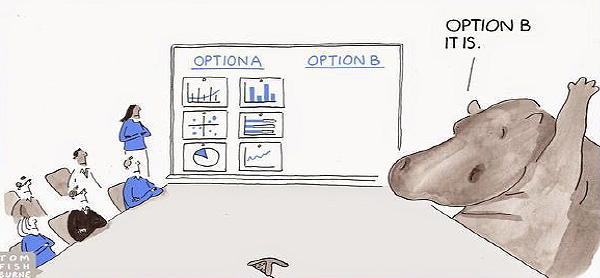

We know there are people who get ideas from intuition. Some of these ideas blossom into innovations that really make a difference. There is a saying – “no idea is a bad idea” which is another example of people dismissing science. Data science is the best way to test an idea and estimate its potential. It reminds us how dangerous it can be to trust ideas that come from HPPOs (Highly Paid Person’s Opinions). These ideas are neither good nor bad; but they are dangerous if they are not data-driven.

I asked Josh how he filters out bad ideas.

To build upon that idiom – “no idea is a bad idea” let’s define bad ideas as ones that result in hurting the business. In the specific cases of design and innovation, we can also say that bad ideas are the ones that hurt the consumer/user experience.

Bad ideas, however, ARE NOT the ideas that fail. Sometimes, failure and lateral movement is part of a strategy. Failed ideas create learning, and lateral movement in value can open up new opportunities.

There are common traits, in my experience, with all bad ideas – ego-driven, unmeasurable, not measured, and uninformed decisions. This is common knowledge, yet so often, these are the ingredients for highly-budgeted flops in the market.

When I was working in advertising, we grumbled at large initiatives that stemmed from executives showing their latest creative briefs to their teenage offspring for a “fresh look.” Their adoration for their developing children, though admirable, would become the next bomb of a campaign. While ego is a common attribute amongst creatives (like myself), unpaired with pragmatism, data, problem framing, and risk assessment becomes merely a form of self-expression. It is essentially art without awareness of its world.

The science of ideas

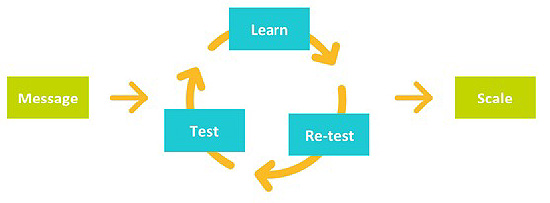

Is there a science to validating and measuring ideas? From my experience, a Testing Center of Excellence (TCoE) uses the scientific method to demonstrate incrementality against control groups which leads to scalable ideas. CoEs are a clearing houses for innovation, where people bring ideas and use data science to determine when to invest. It is a feedback mechanism and a welcome invitation to everyone at the firm who has an idea about how to improve. It should be positive and fun, not a committee to kill ideas. At Hansa, we embrace continuous learning and illustrate it as a Test-Learn-Scale iteration:

The value chain, much like a supply chain, is the chain of inputs that need to happen in order to create a finished product. Along this chain, are different groups (e.g., designers, project managers, engineers, QA specialists) that pour their hearts into a product. As the product cascades closer to the end, the less risk the less ambiguity – the product is being formed into a tangible, consumable thing. Validation testing comes towards the end – having it too early confirms the wrong hypotheses or tells you nothing; too late in the process consumes more resources to fix.

Luckily, with simple tools, we are able to find the right moments to implement this.

- Pre-Build – User testing with a prototype allows us to test designs before the engineers even build anything. It confirms experiential hypotheses before allocating large budgets and time.

- Pre-Launch – By the time the build is done, UAT (User Acceptance Testing) and QA (Quality Assurance) creates a screen to pre-launch that allows for matching of design intentions and alignment with project goals.

- Deployment – At launch, A/B testing and a slow-rollout (starting with 1% of the audience and slowly scaling), allows for a scientifically sound method of result assessment of the project. This approach has become common practice in the tech industry, ensuring the lowest risk at an efficient rate of deployment.

After talking to Josh, I realized UX is a mix of science and art, and that the UX process benefit from the scientific method. So let’s agree to be data-driven and tell our HPPOs to get us coffee for a change.

Roy Wollen has led some of the top marketers in industries such as travel, financial services, b2b and multi-channel retail. Roy is a consultant at heart and solves client problems using marketing technology and analytics. Roy is President at Hansa Marketing Services and an adjunct lecturer at Northwestern University, where he teaches Digital Analytics.

Roy Wollen has led some of the top marketers in industries such as travel, financial services, b2b and multi-channel retail. Roy is a consultant at heart and solves client problems using marketing technology and analytics. Roy is President at Hansa Marketing Services and an adjunct lecturer at Northwestern University, where he teaches Digital Analytics.

Photo by Fakurian Design on Unsplash.

2 comments