“I need you to understand that people don’t have conversations where they randomly recommend operating systems to one another.” – Likelihood to Recommend Survey Respondent.

In just this past week, I’ve been asked some version of the question, “On a scale of 0-10, how likely are you to recommend [Company Name] to a friend or colleague?” at least five different times. Microsoft asked me my likelihood of recommending them with a pop-up when I logged into my computer one morning. My bank asked me through its app. A grocery store texted to ask me after a curbside pickup, and even the auto repair shop where I changed my car’s oil wanted to know how likely I was to recommend them.

Likelihood to Recommend Surveys Are Popular

This single-question survey, developed by consulting firm Bain & Company, has become a staple of marketing research practitioners as a way to gauge customer loyalty and predict future growth. (Some versions also have a follow-up open-ended “Why?” question). The theory is that when a large proportion of customers report a high likelihood to recommend the company in the survey, it is a signal of strong customer loyalty and a harbinger of growth.

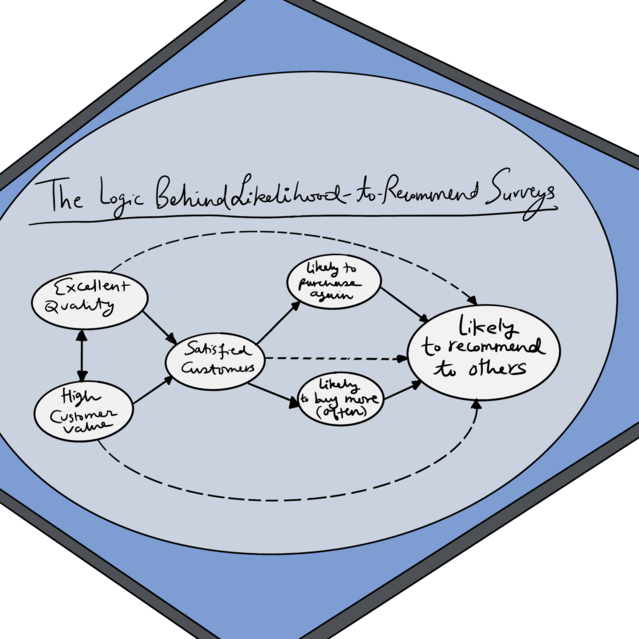

After all, why would you be likely to recommend a company to others unless you were a loyal patron yourself? Customer loyalty, in turn, is dictated by positive prior experiences with the company. Satisfaction is a prerequisite for customer loyalty. And finally, a high degree of customer satisfaction signifies that the company sells good products and services and offers a high degree of value. This framework is shown in the figure below and provides the logic for using likelihood to recommend surveys.

Likelihood to recommend surveys have become popular because of their simplicity. The survey is a quick and relatively inexpensive way to get a sense of what customers think and their future intentions. Companies use the survey’s results for monitoring, as motivation to improve their products and services, and even for compensating employees. As consumers, we’ve become used to constantly being asked the “How likely are you to recommend” from numerous companies that we patronize as a matter of course.

Speed and simplicity are strong suits, but they fall short in other ways.

In this post, I want to explore the downsides of likelihood to recommend surveys. Despite widespread use, there are serious limitations that most consumers and managers who employ these surveys do not know. I want to draw particular attention to the fact that asking someone how likely they are to recommend a company ignores the psychology behind the question’s activities.

The Limitations of Likelihood to Recommend Surveys

An extensive academic literature has discovered the limitations of likelihood to recommend surveys. Longitudinal studies conducted using longer surveys including satisfaction, loyalty, and recommendation questions find that satisfaction and loyalty questions are as effective at predicting the company’s growth as the likelihood to recommend question. One paper has even found that “metrics based on recommendation intentions (net promoters) and behavior (average number of recommendations) have little or no predictive value [in predicting future business performance].” In practice, there are numerous instances of company executives extolling the power of likelihood to recommend surveys to Wall Street analysts and investors, but virtually no data-based evidence is available in the public domain to validate these claims.

There are also other concerns as well. Some practitioners argue that this method focuses only on keeping existing customers, not getting new ones, which is more important for business growth. The survey ignores customers who have stopped purchasing and also potential customers who have not yet purchased from the company. Another issue is that the method only considers the company without any insight into its competitors, nor does it offer specific guidance on how to increase the likelihood of customers’ recommending the company.

There are many other limitations of likelihood to recommend surveys in this literature, but this suffices to make the point that there are significant problems with this method despite its constant use by companies. But that’s not all. There is one even more glaring psychological flaw with likelihood to recommend surveys.

Recommending Companies or Brands Is Not Commonplace Behavior

Returning to the five companies that asked me my likelihood of recommending them within the past week, I confess I’ve had decent customer experiences with all five of them. If they’d asked me how satisfied I was with any of them, I would have said ‘very satisfied.’ If they’d asked me how likely I was to continue patronizing them, again, I would have said very likely.

However, to the question of how likely I was to recommend them, I responded with a 0 or 1 in every case. I am highly unlikely to recommend any of them. Why? I was not deceptive, sneaky, or flippant in my answers. Nor was I trolling them. I like their products and services just fine, which is why I patronize them in the first place. It’s just that in the course of my everyday activities, I don’t go around recommending companies to people willy-nilly.

As far as I can recall, no one has asked me to recommend a computer operating system or a grocery store or a bank to them in a very long time. Nor have I had the occasion to recommend a dish soap, mayonnaise, toilet paper, movie theater, gym, or any number of other products and services that I buy and use. I was being honest when I said that my likelihood of recommending any of the five companies to a friend or colleague is very, very low.

My concern with likelihood to recommend surveys, then, has to do with the psychology behind the behavior of recommending something. The survey question is not aligned with the psychology behind the act. Recommending the dozens of products and services that we buy and experience daily is not something that comes naturally or routinely to most of us. What’s more, it’s not even feasible to keep recommending products and services. We have far more significant and meaningful things to talk about with our friends and colleagues than recommending them different brands.

The nature of our recommendation behavior means there is an asymmetry in how we respond psychologically to our relationships with different companies and brands as consumers. While it is true that we need to have a satisfying experience first and become loyal patrons of a brand before we will recommend it to others, the reverse is not the case. We can have perfectly good consumer experiences and become loyal customers without ever recommending the company.

When a consumer reports a high likelihood of recommending the company in a survey, the chances are high that they may be responding mindlessly, in response to a behavioral script. Where market researchers are concerned, there’s another even more troublesome possibility. When someone gives a low likelihood to recommend, it may reflect their general hesitancy to recommend things, not how they feel about the company’s performance. Managers who use likelihood to recommend surveys for business decisions and consumers who answer them should know this limitation.

Utpal M. Dholakia, Ph.D., is the George R. Brown Professor of Marketing at Rice University.

Utpal M. Dholakia, Ph.D., is the George R. Brown Professor of Marketing at Rice University.

Great article about a practice I often wonder about. It would be nice to see some alternative examples or more effective questions.

Hi Lisa – thanks for your comment. Funny thing about that topic, we’re in about a dozen conversations right now that all have something to do with better / deeper / more meaningful customer sentiment metrics. The questions are only one aspect of the problem. What seems to be vexing to a lot of the orgs that we speak with is that LtR and NPS surveys only speak to what happened and don’t really offer much in the way of predictive / future behavior.

Great article about a practice I often wonder about. It would be nice to see some alternative examples or more effective questions.

Hi Lisa – thanks for your comment. Funny thing about that topic, we’re in about a dozen conversations right now that all have something to do with better / deeper / more meaningful customer sentiment metrics. The questions are only one aspect of the problem. What seems to be vexing to a lot of the orgs that we speak with is that LtR and NPS surveys only speak to what happened and don’t really offer much in the way of predictive / future behavior.

I’ve stopped replying to surveys since this question become the be all of surverys. Every survey I have taken has it, and several that is the only question. Which leads me to assume that this is not a request for my feedback, but simply an attempt to push me to advocate whatever the product is for free to others.

It comes across as mindless patronizing junk and after seeing it I think far less of the company for attempting to use it. But then again, I’ve stopped doing surveys,

I’ve stopped replying to surveys since this question become the be all of surverys. Every survey I have taken has it, and several that is the only question. Which leads me to assume that this is not a request for my feedback, but simply an attempt to push me to advocate whatever the product is for free to others.

It comes across as mindless patronizing junk and after seeing it I think far less of the company for attempting to use it. But then again, I’ve stopped doing surveys,